Before 1906: Jefferson and the 1800's

BROCKENBROUGH HILL

While Thomas Jefferson was transforming an old farm field into his academical village, Carr's Hill stood across the road, undeveloped in the shadows of great trees. The earliest known owner of the original eighty acres was a farmer named James Burnley. He had died debt-ridden in 1803, leaving the property to his daughter Mary, who married Daniel Piper. The couple then subdivided the land, and in 1829 sold the forty-three acres of upland bordering Three Notched Road, now known as University Avenue, to the University's then then proctor, Arthur S. Brockenbrough, for $1,065.62. Mr. Brockenbrough had been hired in 1819 to oversee the construction of the University. He died in 1832 and left the steeply sloping forty-three acres across the road to his wife, Lucy Brockenbrough.

STUDENT HISTORY

The land Lucy Brockenbrough inherited would become her living. By the time of her inheritance, all of the University's original 109 student rooms in the academical village were fully occupied. In 1833, Mrs. Brockenbrough opened the first boarding house for students on and then known as Brockenbrough's Hill. One of the earliest purveyors of housing off the Grounds, she kept Brockenbrough Hill until 1849, housing twelve students, five white children, and fifteen enslaved persons. In their archaeological report to the University, Rivanna Archaeological Services notes that this large number of enslaved workers might "represent labor that was leased to the University on an annual basis, or it might also suggest that some type of agriculture supplementing the boarding house income was also practiced in the bottom lands along Meadow Creek."

Mrs. Brockenbrough operated the boarding house until her death. Then in 1849, as a result of a lawsuit first brought in 1822 by a creditor of Mr. Burnley, it was sold to Maximillian Schele de Vere, a professor of modern languages at the University, for $2,370, an amount that was to cover all the debts against the Burnley estate.

CARR'S HILL

Three years later, Mr. Schele de Vere sold Brockenbrough Hill for $4,460 to Thomas Jefferson Randolph, University rector and grandson of Thomas Jefferson. Brockenbrough Hill became Carr's Hill in 1854, when the property was sold again to Mrs. Dabney S. Carr for Mr. Randolph's own purchase price. According to a notation he made during the course of the sale, Mrs. Carr was already living on Carr's Hill when she bought it from him. She may have been renting a house as a residence for herself, or she may have been operating one as a boarding house. After the sale, she continued the student-boarding trade on the hill.

The boarding houses proved to be more popular with students than did the original "dormitories" of the academical village. This preference for boarding houses had something to do with the University's growing population. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the University's enrollment stood at 645, third highest in the nation, exceeded only by Harvard and Yale. The allure of Carr's Hill, however, must have also had something to do with Mr. Jefferson's most vaunted value, freedom – and perhaps the quality of the food. So popular was this early off-Grounds housing that one of the University's early historians reported that Mrs. Carr sometimes had "as many as 50 young men seated in her comfortable dining room."

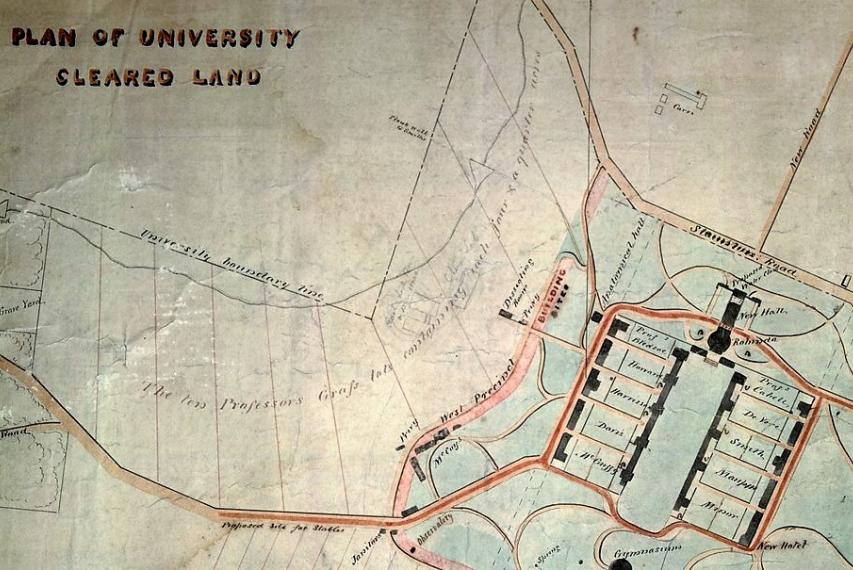

Carr's Hill continued to change hands after that, but the name became permanent. In 1863, Mrs. Carr sold Carr's Hill to Addison Maupin for $30,000, probably in Confederate dollars. At the time, Mr. Maupin was the manager of the University's dining halls and brother to Socrates Maupin, the chairman of faculty for the University, an administrative officer whose duties most closely resembled that of a university president. Mr. Maupin kept the property until July 1, 1867, when he sold it to the University of Virginia for $10,000. The Board of Visitors at that point considered the property "indispensable to the University's purposes." As a holding action, Board of Visitors minutes of June 29, 1871, indicate that Carr's Hill was purchased "to prevent the occupation of the grounds by objectionable tenants."

UNIVERSITY OWNERSHIP

Carr's Hill officially became one of the University's holdings, and student housing on the hill became the University's responsibility. In 1867, during its first year of University ownership, the rustic, two-story frame-built Blue Cottage – the first structure built on Carr's Hill (circa 1837) and located down the hill from the current president's house – caught fire. Because of the press of a growing student body, the University reconstructed that building and erected a new set of dormitories, built in brick and containing thirty-two rooms, almost immediately.

As populated as Carr's Hill was by students housed there, it was also used by students as an area for both recreation during peacetime and military drills during war. Over the years, small gymnasiums were placed at various points on Grounds, including on Carr's Hill. Sheltered by trees, they consisted of "clusters of horizontal and parallel bars, swings, and poles." These early gymnastic facilities prefigured Levering Hall, an addition to Hotel F, which dates to 1857, and Fayerweather Gymnasium, built on Carr's Hill in 1893. Also on Carr's Hill, students played baseball and basketball, while the social club, Hot Feet, performed plays, and students soon to be soldiers mustered for battle practice.

Carr's Hill was also the location of a prewar raising of the Rebel flag, political theater reminiscent of protests during a later era in United States history. One day, a group of University students hoisted a Confederate flag atop the Rotunda. The excitement of that act of rebellion led authorities to cancel classes. The chairman of the faculty told the students that they would not be prosecuted for their small uprising if they took away the flag. It was removed to Carr's Hill, where, for a time, it flew from a ramshackle dormitory.

THE CIVIL WAR

During the war, student enrollment fell drastically at the University. Not many men were left on Grounds: in 1862, there were only forty-six students and a few old professors. Also present were a number of doctors, who served in the hospital set up in the Rotunda after the first battle of Manassas, and later in the buildings of Dawson's Row and in some Range rooms, caring for sick and wounded Confederate soldiers, one thousand of whom are buried in the University's graveyard. The war raged around Virginia, but Charlottesville and the University were largely spared the devastation of the rest of the state.

On March 3, 1865, rumors flew. Having defeated Confederate troops at Waynesboro, General Philip Henry Sheridan was said to be marching on Charlottesville. Fearing that his troops would ravage the University of Virginia as Union troops had done at the Virginia Military Institute, a University delegation prepared to do what had to be done to ensure the safety of the school. The University rector, Colonel Thomas L. Preston, together with the chairman of the faculty, Socrates Maupin, and John B. Minor, a professor of law, met General Sheridan's advance guard, led by General George Armstrong Custer. Mr. Minor waved a white handkerchief attached to his walking stick. General Custer greeted them peaceably and he posted a guard outside the University to protect the Grounds while his troops were encamped on Carr's Hill.

AFTER THE WAR

After the war, while the strict architectural control that Thomas Jefferson had exercised in building the University held across the street, more and more trees were cut down, and one homely building after another arose on Carr's Hill. The buildings, especially the dormitories, were heavily used but poorly maintained. In a report to the faculty of 1886, the proctor noted, "This entire range of buildings is in very bad condition. The roof is of shingles and leaks badly – the dormitories on the ground floor are low and damp. Twelve of them are unoccupied and uninhabitable and will so remain, unless something is done to better their condition. There is no gas, no running water, and less of the convenience and essentials to healthful living than on any part of the University grounds."

The chairman of the faculty said that the improvements to the Carr's Hill dormitories as recommended by the report were too expensive. But one year later, gas and water lines were added, and, in 1888, latrines were installed. That same year, the Board of Visitors funded the construction of a dining hall on Carr's Hill. Unfortunately, these additions were too little, too late. The dormitories continued to deteriorate.

Especially meaningful to the history of the University was a problem on the hill not recognized until the fire that devastated the Rotunda in 1895: low water pressure, which affected the dormitories in a minor way, but proved to be disastrous when fire fighters attempted to pump water to quench that fire. A water tank for drinking and for fire safety was installed on Carr's Hill in 1895, following the fire. Still, even with these improvements, the University continued to lose money by rooming and boarding students on Carr's Hill.

On May 1, 1905, its dormitories closed down. Visitors to Carr's Hill can still see a remnant of those dormitories. Although the major section of the L-shaped dormitory was destroyed when the president's house was built, there remains today a two-story brick house behind the herb garden. Carr's Hill Cottage is still in use today.