1906 - 1909: Design & Construction

GROWTH AND EXPANSION OF THE UNIVERSITY

As the 19th century drew to a close, the University continued to grow in every way - enrollment, size of the faculty, the physical plant, and the complexity of its operations. Several buildings - Brooks Hall, the University Chapel, Fayerweather Gymnasium and an annex to the Rotunda - both accommodated this growth and changed the University's geographical orientation from south to north.

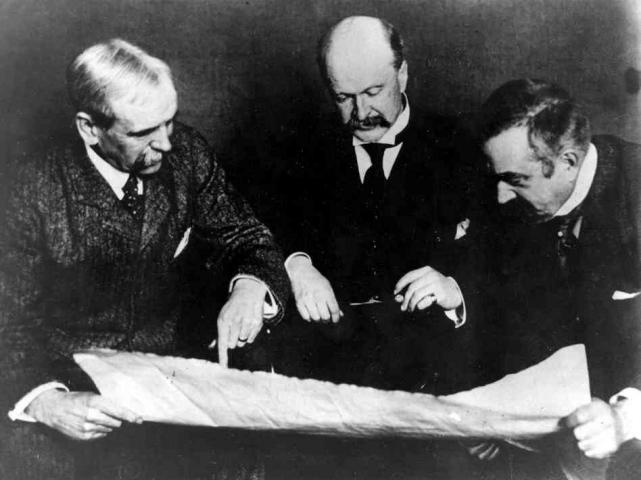

MCKIM, MEAD & WHITE COME TO UVA

On Monday, October 28, 1895, following the devastating fire that destroyed the Rotunda, the faculty building committee hired the firm of McDonald Brothers of Louisville, Kentucky, to advise them on the rebuilding of the University. The committee emphasized that the appointment was to be merely advisory, and that later, an architect of national reputation would be hired to carry out the design and construction for the Rotunda and new academic buildings. Stanford White and his firm, McKim, Mead & White, were chosen as the architects of the restored, expanded, and finally enclosed Lawn.

To Stanford White, the addition of Cabell, Rouss, and Cocke Halls seemed imperative. He was not set on their location opposite the Rotunda, however. The Board of Visitors made the decision to turn the Lawn into a quadrangle. In the end, Stanford White's restoration of the Rotunda and the triad of buildings to its south never ranked among his greatest work. On the other hand, his work at the University met all expectations and requirements. Cocke, Rouss, and Cabell fit seamlessly into the academical village, while the exterior of the Rotunda was faultlessly Jeffersonian.

The work, however, had not been easy. The chaotic decision-making process at the University nearly drove him "crazy," he reported. Not knowing exactly who would be giving him orders and serving as a go-between for rival members of the faculty and board was not a position any architect would wish for himself.

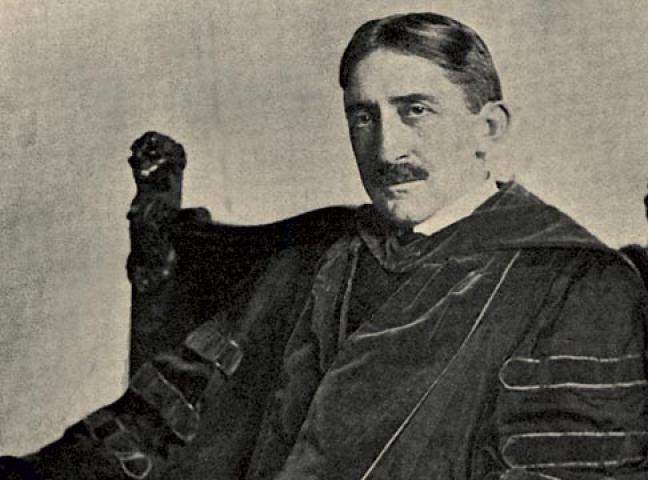

Mr. White survived the job. The University's system of management, however, did not. It was time that the University had a president, and in 1896, the faculty committee urged the Board of Visitors to appoint one. After first being turned down by law alumnus Woodrow Wilson, the University turned to Edwin Alderman, who had built a record of achievement as president of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and at Tulane University in New Orleans. He was inaugurated on Mr. Jefferson's birthday, April 13, 1905.

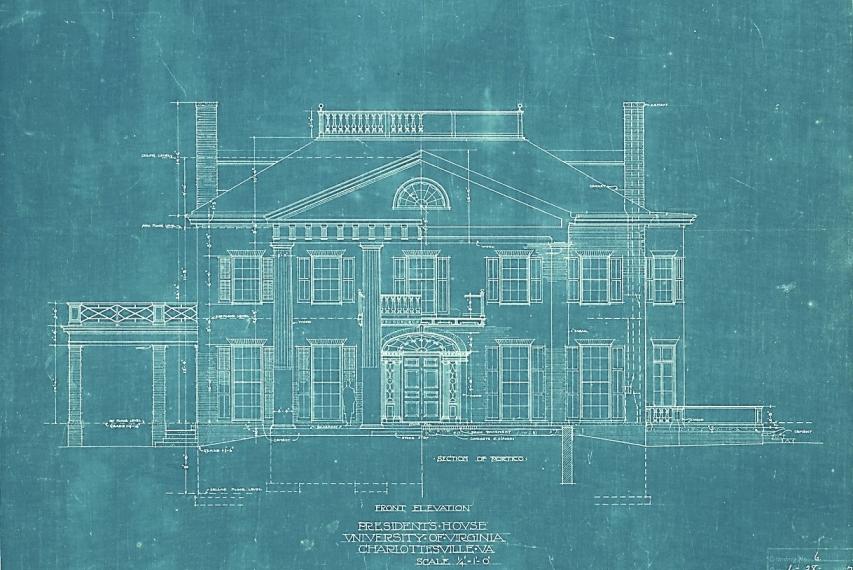

A HOUSE FOR THE PRESIDENT

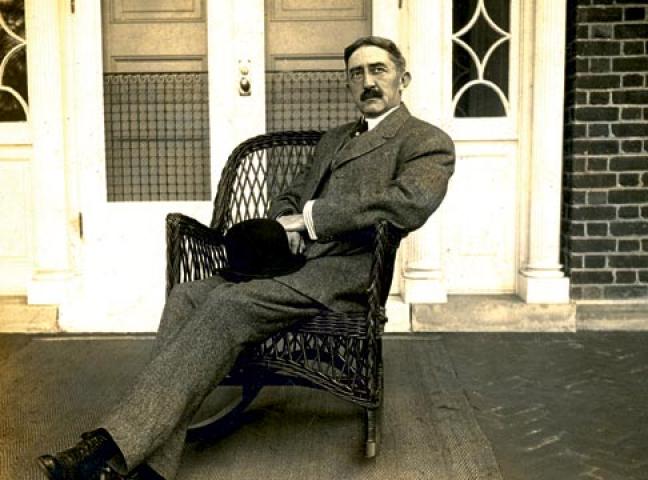

Edwin Alderman and his wife, Bessie, sought a hard-working house to accommodate all the public events they anticipated, a house offering public spaces on the first floor and private living space on the second. It would function not unlike the professors' pavilions that lined the Lawn.

William A. Lambeth, who served the University as professor of medicine, chairman of the Department of Physical Education and superintendent of buildings and grounds, was already at work planning a suitable house for the University president. He was serving as construction manager of the hospital expansion when he took on the construction of Carr's Hill.

In March of 1906, Dr. Lambeth had a roster of six firms he asked to develop proposals based on a detailed description of the requirements of the house. But on May 1, 1906, Mr. Alderman wrote McKim, Mead & White a letter of inquiry, and Stanford White was chosen as architect for the president's house and a new refectory.

PROTEST FROM LOSING FIRMS

The principals of the losing firms were miffed. The disappointed Taylor and Hepburn from Norfolk wrote to President Alderman requesting that its drawings be returned and complaining that the competition was not genuine:

"We hear … that you have entrusted the President's house to Messrs. McKim, Meade and White. … We are not a little surprised to hear of such a decision on the President's house, as the last thing we heard was that you preferred our exterior and New Orleans plan to anything submitted. As the reported winners do not go into competitions, we are at a loss to understand what has happened to bring them the commission instead of its being granted to a competitor."

THE NEW ORLEANS PLAN

Besides the writer's pique, his reference to the "New Orleans plan" is interesting. The term can be found elsewhere in other letters to and from President Alderman. Stanford White refers to "the New Orleans House" in a letter to Mr. Alderman in which he compares his tentative plans for the president's house to the Aldermans' preferred plan. The crayon drawing of the Carr's Hill house plan, the "Tentative Statement of Plans for President's Residence," and the plan submitted by the New Orleans architect Francis J. MacDonnell all reflect the so-called New Orleans plan. Which one served as the Alderman's inspiration is unknown.

What is known is that Mr. MacDonnell was a member of the firm that designed a house pictured in the series New Orleans Architecture and identified by Garth Anderson, the University of Virginia facilities historian, as the doppelganger of the University president's house. Mr. Anderson observes that this book reveals a "startling finding," startling in that 5603 St. Charles Avenue so closely resembles the final plan for Carr's Hill that it calls into question the authorship of Carr's Hill.

He points out the similarity: "With its porte cochere on the right side of the house (when viewed from the front,) it appears to be a mirror image of Carr's Hill. Though the McCarthy residence has full fluted columns across its entire façade and quoins, the massing and entrance are very similar to Carr's Hill."

He notes that the McCarthy house was located in the (Tulane) University District in which the Aldermans lived and was completed in 1903, in time for the couple to have visited it before moving to Charlottesville. He also mentions that the current owner of the house, Robert Ramelli, "has reviewed the original McKim, Mead & White drawings for Carr's Hill and he finds them to be a mirror image of the plans for his home, which is in its original condition." The fact that the Aldermans perhaps had a chance to see the house is made more significant by the fact that Francis MacDonnell had also submitted a proposal for the Carr's Hill project, a plan about which he wrote to President Alderman:

Dear Sir:

I have expected for some weeks to hear from you regarding your proposed residence for which I made sketch plans early in April. I will thank you for some information in the matter and hope that you have decided to build from my design.

Very truly yours,

Francis. J. MacDonnell

WHITE'S PROPOSALS

For his part, Stanford White was not enthused about the New Orleans plan. In a letter to President Alderman, he points out, a bit unnecessarily, that the future structure should fit the surrounding Jeffersonian architecture. He also notes that, unlike the New Orleans plan, it should not have a porte cochere, which would "hurt the dignity of the house," and that it should just generally be more imposing than the plan the Aldermans showed him. That plan, wrote Mr. White "was really a semi-detached city street villa, and, although it had many modern and convenient ideas, nevertheless, its whole arrangement was that of a house without the balance and dignity which it seems to me that the President's house of the University of Virginia, crowning its noble hill, should have."

Instead of the New Orleans plan, Stanford White proposed two alternate plans, which seem to be no longer extant, and which Mr. Alderman rejected in a letter of June 16, 1906. Plan B is unsatisfactory, according to this letter, because the living room [is] entered upon directly from the porch. This would no doubt be delightful for a summer home or lodge, but for a winter house, it seems to me that two elements are lacking, viz: comfort and privacy. As to scheme A, the fundamental departure from the only plans we had in mind make it almost impossible for us to render an opinion. It falls so far short of what we had hoped for, that I fear it practically means considering a new set of ideas on the subject.

Plan B has superficial problems, shortcomings having to do with the wrongly shaped windows, wrongly sized steps, misplaced doors and fireplace, missing lavatory, and other similarly nonstructural issues. Plan A's problems are global and irreparable. It fails to approximate the New Orleans plan. Mr. Alderman promises to return the two schemes by mail and asks for another plan. He also notes that Mrs. Alderman is to be in New York on June 22, and that she plans to call on Mr. White in his office. (This visit was to be three days before Stanford White was shot to death in Madison Square Garden.)

On June 20, Mr. White wrote back to President Alderman. He explains to Mr. Alderman that he and Mrs. Alderman have misunderstood the plans A and B:

"I fear that you have taken the rough sketches, particularly of the exterior, too seriously as representing our final judgment. The sketch of the exterior was intended only to dictate roughly the height of the building and its general style, to enable Dr. Lambeth to make up an estimate of cost; and the details of the windows, doors balustrades, roofs, etc., were not even considered.

These are matters which will require serious study and I am sure that I shall be able to give you a design which will please you, and which will be in strict accordance with the old buildings."

Mr. White goes on to explain that in "scheme B," the main entrance does not let onto the living room. "My idea was to place the main entrance at the side along with the porte-cochere entrance, and not even to lead a path to the large front portico, and, by its treatment, to give it as much privacy as any porch placed on the front of a house can have. I shall explain this clearly to Mrs. Alderman when she comes, for, in my opinion, plan B will make a far better house, and one that can be built within the amount of your appropriation." About "plan A," he notes that he will revise it according to the Aldermans' criticisms, but does "not see how it will be possible to build such a house for the money available." According to this explanation and the penultimate sentence of the letter, "if you definitely reject the plan with the large library along the front," we can see that plan A does not resemble in any way the ultimate design of Carr's Hill. The actual design may derive from the University district house located around the corner from Mrs. Alderman's childhood home, or it may be, as Richard Guy Wilson has explained, a design typical of the McKim, Mead & White oeuvre, a house that they produced a number of times elsewhere, a perfectly understandable repetition given the untimely death of Stanford White.

STANFORD WHITE

Stanford White was a wildly gregarious and creative force during the so-called Gilded Age. In this era, from the 1870s to the 1890s, wealth was accumulating in the hands of a few who, with much money on hand, spent it conspicuously on clothing, travel, jewelry, estates, and summer houses. A member of the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, Mr. White catered to the superwealthy, building them ornate and expansive town and country homes, while also designing such civic masterpieces as the second Madison Square Garden (demolished in 1925), Washington Square Arch, and Madison Square Presbyterian Church. At the University of Virginia, his Cocke, Rouss, and Cabell Halls were restrained examples of his work, while the interior of the rebuilt Rotunda was somewhat more exuberantly typical. (Mr. White's version of the Rotunda was restored to Thomas Jefferson's original design in 1976.)

While his architectural designs were drawn with exquisite care, he lived his life recklessly. He was careless with his money and in his relationships with women. By the end of his life, he had lost both the fortune that he had earned and large amounts of money he had borrowed, mostly from his wife, Bessie Smith White of the Smithtown, Long Island, Smiths. He had also romanced a number of very young women. Such romancing was expensive, especially for one so imprudent with earned and borrowed money, money that burned holes in his pockets until he used it to support, dress, and bejewel many of the nubile women of the New York theater. He also used it to buy art and artifacts and beautiful home furnishings. Still, although financially devastated, he was not socially ruined in spite of extravagantly bad-boy behavior, wooing underage women, and living it up at large, orgiastic parties. The goings-on of Stanford White at these parties regularly hit the headlines. Still, he continued to be a sought-after guest at high-society dinner parties; unlike financial ruin, social wreckage happened to Stanford White and his family posthumously.

His death was to be as extreme as his life, and provided far worse publicity. On the evening of June 25, 1906, Stanford White was shot dead in an act of revenge by the bilious millionaire Harry Thaw, husband of the chorus girl and former Stanford White lover, Evelyn Nesbit. Five years earlier, Mr. White had witnessed her performance in the Floradora musical revue, and had found someone to introduce them. As was usual with Mr. White, one thing led to another. The relationship was long over when Harry Thaw bullied his wife into telling him about it.

After Harry Thaw's arrest, his mother hired him expensive and imaginative lawyers, who devised the first ever temporary-insanity plea. During the trial, Evelyn Nesbit Thaw testified that Stanford White had drugged and raped her soon after their first meeting. This violation, she claimed, was what had driven her husband to insanity and then revenge. During the trial, the defense told stories of Stanford White's love life, details that inflamed public opinion against the victim and in favor of his killer. In the end, Harry Thaw traded jail for an insane asylum, having been found not guilty by reason of temporary insanity. Cut down in his prime with many more buildings to design (one of which would have been Carr's Hill), Stanford White left behind a great Gilded Age legend: of creativity rewarded and appetites punished.

THE HOUSE

With the death of Stanford White, his firm apparently acceded to the Aldermans' wishes for the design of the president's house. William Kendall of the firm took over the project. The New Orleans plan, designed for entertaining guests on the first floor and housing family on the second, was put to paper. What they built then has changed (mostly cosmetically) over the years, but still offers the room and circulation pattern ideal for its uses.

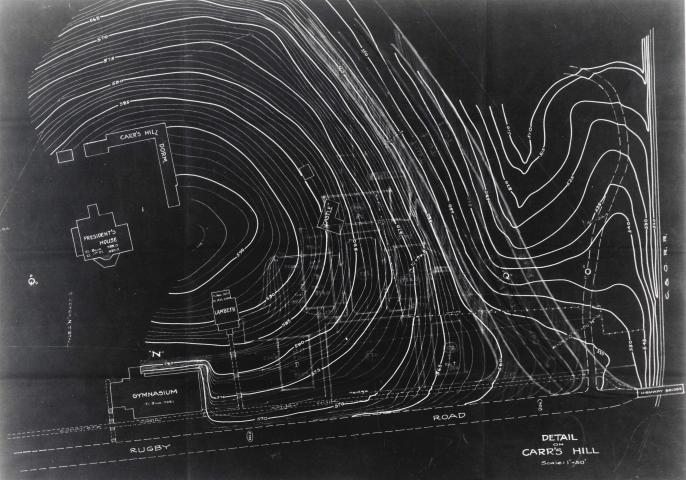

Work on the house began with the terracing of Carr's Hill in 1907. In the course of construction, most of the dormitory buildings on Carr's Hill were demolished, except for part of the old L-shaped dormitory, originally servants' quarters and now the Carr's Hill guest house; part of the refectory, now used as an office; and the venerable Buckingham Palace, also today used as guest quarters. In 1908, the carriage house (the president's garage) was completed, possibly with wood and brick from the torn-down structures on the hill. In 1909, the house itself was finished. The total cost of construction was $28,837.

The house as it is today, excellent in form and function, owes as much to the Aldermans' persistence in seeing that their vision was realized as it does to the professionals who planned and built it. For twenty-six years, it served the Aldermans well, and for a hundred, the University. From the beginning, it was agreed that the house was a success. William Lambeth, ratifying the idea that McKim, Mead & White might improve on Jefferson, said of it: "The President's House resulted from an effort of Stanford White to give the University an example of a lighter, more airy type of classic form than any left by Mr. Jefferson. Jefferson's types, from the beginning were romanized. Weight, predominating, gave nobility and dignity. The President's House is more graceful than dignified, more beautiful than noble, yet the structure breathes both nobility and dignity."

Part of its impression involves its service as a symbol as well as a place for living and gathering. In 2007, Carr's Hill was placed on the Virginia Landmarks Register and was subsequently nominated to be included in the National Register of Historic Places. The nomination application reads:

Not only since its construction but from its very conception as well, the President's House on Carr's Hill has been a symbol of the drivers of university growth, as well as the harbinger of change to university structure. Its physically commanding design and location have appropriately represented the prominence of the presidency of one of America's leading universities. It retains the essential historic character of the design by McKim, Mead & White, and its integrity is highly intact. The President's House, a conscious attempt to represent physically the preeminence of the office of university president, remains representative of the new era of university history begun with the creation of the presidential administrative structure in 1904.

To be symbolic and functional is a heavy burden on a house, not least because through time cultural alterations change a symbol's associations and a house's purpose. It is a tribute to Carr's Hill that in these past one hundred years, it has stood up brilliantly to such change.